If the Boston & Maine’s network of branch lines in New England had not existed, railway modelling enthusiasts would probably have invented them. After all, these lines represented a made-for-modelling combination of short trains, handsome locomotives and rolling stock, classic structures and stunning scenery.

The HO scale Claremont Branch layout described here was my attempt at capturing the magic of New England railroading. But first, some context…

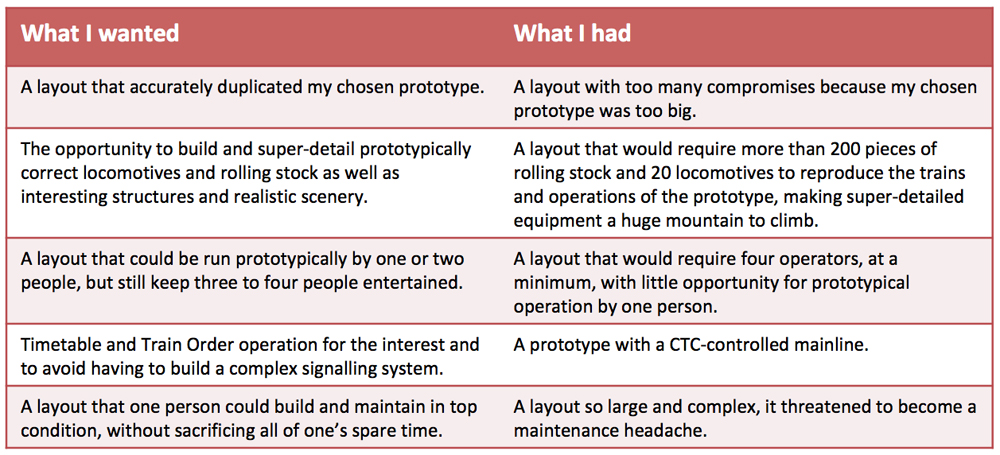

In the late 1990s I realized that the layout I was building in Ottawa, Ontario – based on the Toronto Hamilton & Buffalo Railway’s bridge line between Hamilton and Welland in the Niagara Peninsula – was not right for me. Facing a hobby crisis, I made a list of the criteria for my ideal layout then compared it to what I was actually building. Here’s the list:

The list was a real eye-opener. Somewhere along the journey my railway modelling interests had completely changed and my under-construction TH&B layout no longer represented what I wanted out of the hobby. What to do?

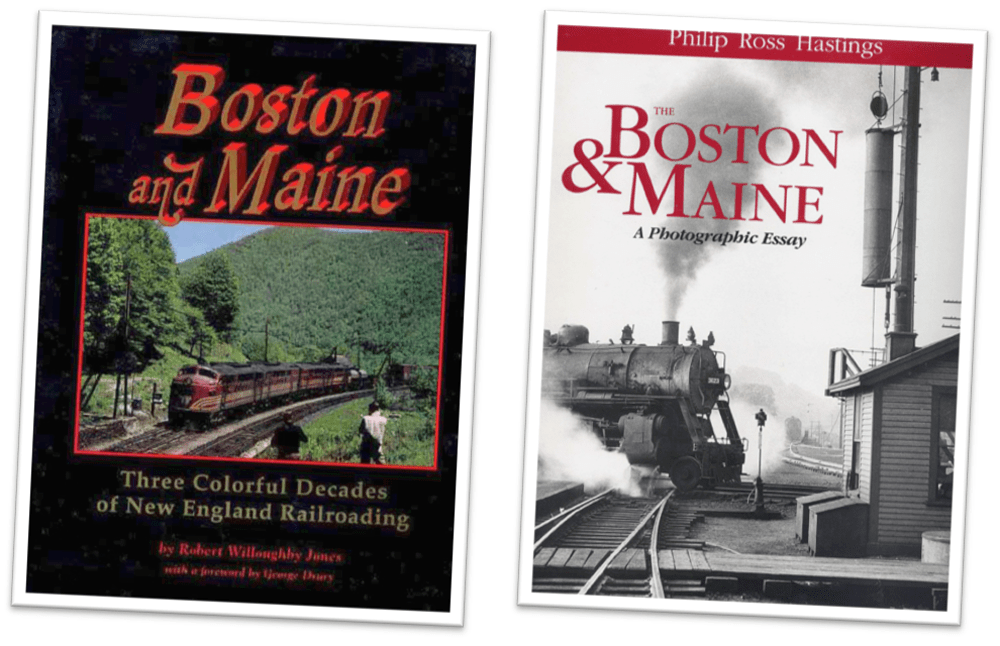

As I pondered this, my friend Mike Hamer was looking for a prototype. He was taken by the TH&B and considered modelling that, but as I looked at his layout space and his own Want List, I encouraged him to instead consider the Boston & Maine. I had a copy of the book Boston & Maine: Three Colorful Decades of New England Railroading by Robert W. Jones and Mike liked what he saw. (I’m pleased that all these years later, Mike is still enjoying the B&M layout that I designed for him.)

In the process of convincing Mike that the B&M was an ideal prototype for him, the railroad started to grow on me. That led me to acquire a copy of The Boston & Maine: A Photographic Essay, featuring the extraordinary photography of Philip Ross Hastings. This turned my railway modelling world upside down.

Hastings’ photos of the Claremont Branch ticked all the boxes for me and a trio of articles by Scott J. Whitney in Railroad Model Craftsman magazine (November 1993-January 1994) provided plenty of prototype information to get me started.

Around 1996 I sold off my TH&B equipment and started collecting B&M models. The TH&B layout sat in place as an elaborate test-track for my new equipment while I planned a new layout. I even built a model of the Claremont Junction engine house based on a two-part construction article by Eric Stevens in the January and February 1953 issues of Model Railroader magazine:

I was about to start tearing out the TH&B layout to built the new B&M project when a couple of moves – first across town, then to another city – forced me to sideline my layout ambitions for a few years. But by 2001, I was in Toronto and looking at how to squeeze part of the Claremont Branch into a roughly 14’x16′ space under the kitchen.

I designed an out-and-back layout, featuring the New Hampshire towns of Newport and Warner, fed by a single staging yard serving as both ends of the line. This was a fairly faithful tribute to the Claremont Branch and – with bonus elements, including a couple of signature covered bridges and my engine house model.

There were a few significant things about this B&M Claremont Branch layout.

First, this was my first “Achievable Layout” – which I defined in my list of what I wanted as a layout that one person could build and then maintain in top condition, without sacrificing all of one’s time, money or other resources. That definition has guided every subsequent layout I’ve built for myself, and forms the basis of any layout advice or designs I’ve created for my friends.

Second, a problem with commercial track switches forced me to relay the track for the entire layout and rather than rely on commercial components I decided to try my hand at hand-laying. While the initial results were rough and eventually contributed to this layout’s demise, this has become an aspect of the hobby that I really enjoy. (This layout was also my first to feature DCC and other things we take for granted today.)

Third, it was my first layout on which I attempted to model not just trains, but jobs: I became fascinated by the idea of translating prototypical procedures such as locking track switches and realistic paperwork as a means of slowing down the pace of operations and extending the apparent size of the layout. This “finescale ops” thinking worked really well and became an essential feature of all subsequent layouts.

Fourth, this was the first layout I built which featured mockups of all the structures, built from quality artist board. This did a lot to both visualize scenes and explain to visitors what I was doing – and I’ve done this on every layout since.

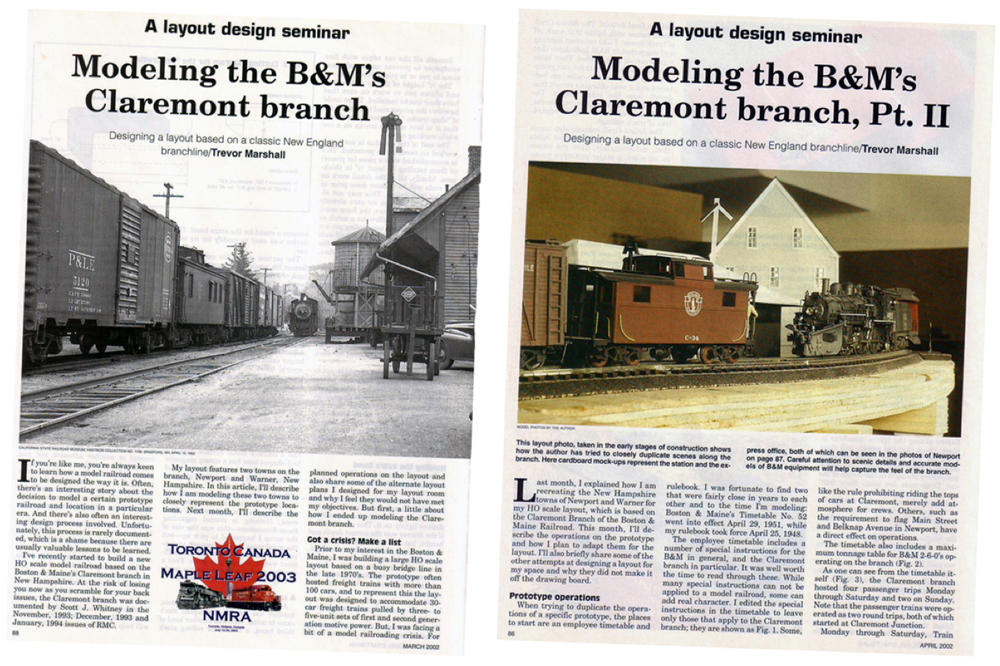

Fifth – and perhaps most importantly – this layout became the subject of my first major piece of writing for the hobby press:

I’d done a couple of smaller features before this, but the Claremont Branch turned into 18 pages spread over two parts, in the March and April 2002 issues of Railroad Model Craftsman. I’m pretty sure this series put me on the radar of then-editor Bill Schaumburg, who became a great friend. I would go on to write several dozen articles for Bill.

So, what happened to the B&M Claremont Branch? Looking back on it, I’d say it was impatience on my part. As I became enamoured with the idea of modelling jobs, I realized the enormous impact that DCC and Sound was having on the hobby.

Sound, in particular, changed everything. It slowed down operations – not just because the sound provided feedback that made engineers realize they were running their trains too fast, but also because one had to stop and think about what one was doing. Whereas in the silent era an operator’s decisions came down to “direction switch and throttle”, now there were considerations such as bell and whistle regulations, lights, and so on. Think of starting a train and crossing a street: with sound, one needed to blow the whistle (two blasts to indicate forward movement, three for a backing move), then start the bell, then open the throttle. Once moving, the bell was silenced. Then, as one approached the crossing, the bell would once again be engaged and the whistle blown (two longs, a short, a long held until the crossing is occupied) – and eventually, the bell is turned off again.

Sound, prototype paperwork, switch locks and other finescale ops elements meant that most freight trains now warranted two crews and most layouts would work quite well – better, in fact – with half the trains on them. DCC technology was central to this, and I knew it would effect huge changes on the hobby.

Sadly, I also realized that the HO scale B&M B15 2-6-0s that were the backbone of my fleet were too small to fit with sound decoders. It was hard enough to fit them with silent ones, which were typically longer than the tenders. In addition, DCC did not yet have the “electronic flywheel” auxiliary power modules that have become ubiquitous today, and those 2-6-0s suffered from electrical pickup problems – especially at slow switching speeds. This was exacerbated by my decision to use stiff-legged steam models and Code 55 rail which, while appropriate for a light branchline in HO, had such a small railhead that reliable connection between wheel and rail was a constant issue.

If I’d waited a little bit longer – a few years – the size of decoders would’ve come down to the point where they’d fit into the 2-6-0s, and I’d probably still be modelling the Claremont Branch today. But I didn’t. Instead, I made the difficult decision to abandon the B&M in HO and move up in scale.

I sold my collection to a B&M enthusiast I know. My next layouts would be in On2 and based on the Maine two-footers – in particular, the slate-hauling Monson Railroad. But that’s a story for another time…

Postscript: I’m still a huge fan of the Boston & Maine. One of the first purchases I made when I started working in S Scale in 2011 was the Flying Yankee streamliner, imported by River Raisin Models. It’s far too glamorous (and big) for my layout, but here it is, posed in St. Williams…