Like many lifelong modellers, I built a number of starter layouts – designs that were driven by track arrangements more than by any sort of coherent plan. The point where I became a modeller of railways occurred in the early 1990s when I started building a shelf layout in a spare basement bedroom based on the Toronto Hamilton & Buffalo Railway at Smithville, Ontario.

It was my first serious layout, and I learned a lot from it – including that layouts don’t last forever: About a year after I started it, I moved from Toronto to Ottawa to pursue a job opportunity and I tore down the layout. The good news is, I ended up with a larger layout space – a finished family room measuring approximately 12′ x 20′ in the lower level of a side split house. And I created a grand plan to build a new version of the TH&B.

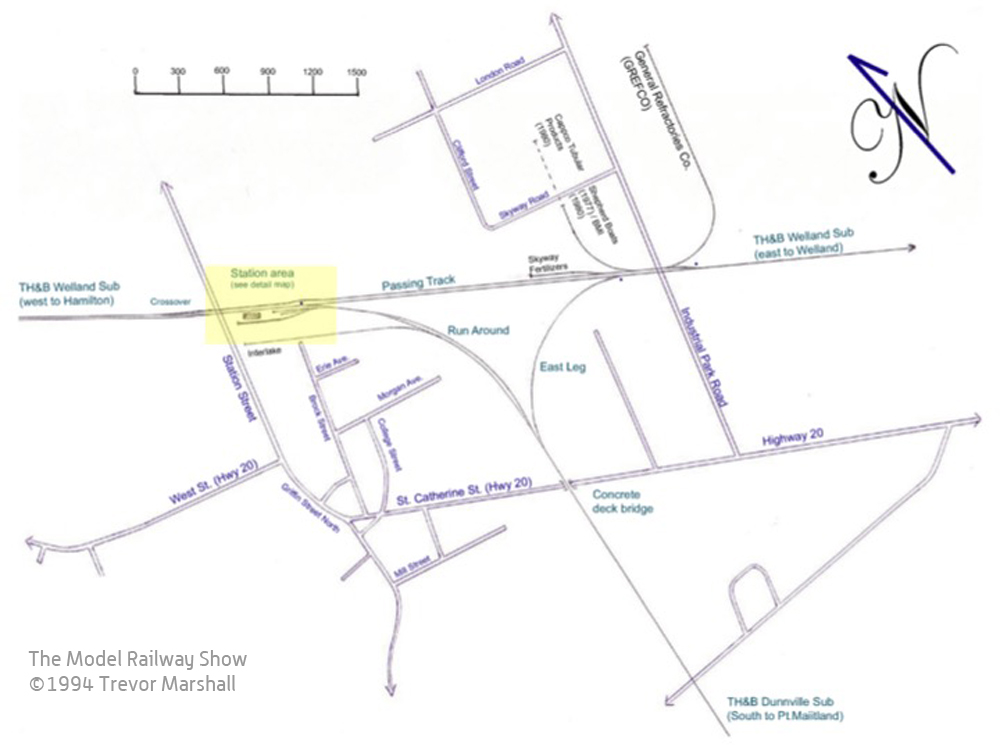

This new layout would be my first – and last – venture into multi decking. The plan involved a pair of two-level decks, and was designed to capture the essence of this busy bridge line that connected Southern Ontario with Western New York. I was modelling the late 1970s, when the TH&B was jointly owned by CP Rail and the then newly-formed Conrail. The layout was designed to support a maximum train length of 30 cars with three locomotives and a van – quite a tall order for a room this size!

The lower level featured the TH&B’s Kinnear Yard in Hamilton. This was where a manifest freight in each direction between Toronto and Buffalo would stop to exchange cars to and from Hamilton. It was also where the TH&B’s belt line left the main track to serve many heavy industries in Canada’s steel city. Kinnear Yard was served by a staging area built underneath it, representing the TH&B’s Aberdeen Yard (the main classification yard in Hamilton) and the route to Toronto.

This deck was very much a freelanced design, bearing almost no relation to reality. But it was intended mostly to support the more prototypical arrangement at Smithville on the upper deck while providing additional play value for operating sessions and I could live with those compromises.

From Kinnear, the mainline would climb a helix to the top deck and Smithville.

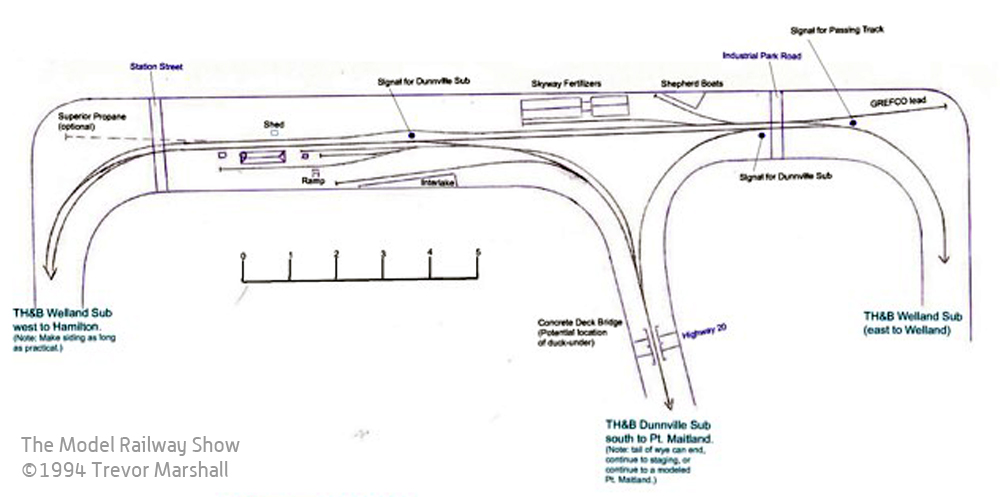

At Smithville, the East Local called out of Aberdeen Yard would serve the local customers and duck down the branch to Dunnville and Port Maitland. The main would continue east to Welland and on to Buffalo. In reality, these two routes ducked below the top deck to another staging area. It sounded complex – and it was – but I had figured out how to make it work.

Smithville would’ve provided plenty of operating fun and if I’d build it as a stand-alone layout I might still be a modeller of the TH&B. But the wooden subroadbed was barely down in the helix when I realized that modelling a busy bridge line – requiring, at a guess, 200 pieces of rolling stock – was at odds with my growing interest in building well-detailed pieces of equipment and structures.

Daunted by the project, I started to find other things to do with my time until I stumbled upon a completely different prototype for a layout: the Boston & Maine Railroad Claremont Branch in New Hampshire, in the early 1950s. It was completely different, and spelled the end of the TH&B.

While I never did get to build Smithville properly, I did build some of the structures for it. I scratch-built the beautiful little section house / handcar shed that stood just to the east of the station. It sat on the layout near the Belt Line wye. I also built models of some of the less distinctive sheds that dotted the property in Smithville.

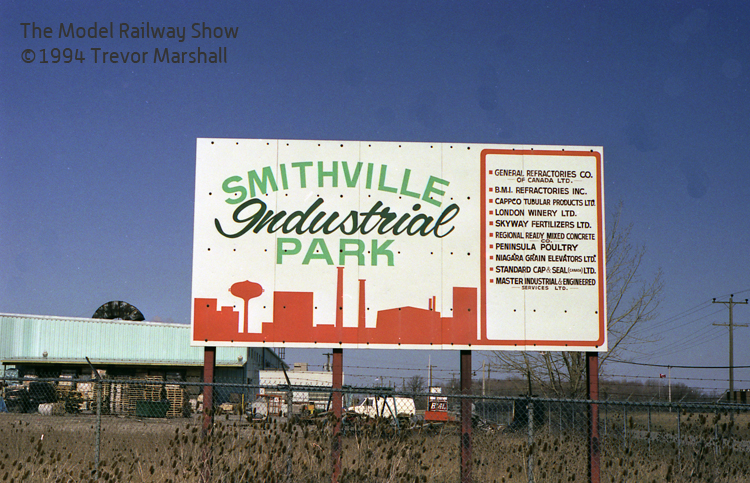

Years later, I would build a model of Skyway Fertilizer – a customer that ran along the north side of the main track in Smithville. This ended up in the industrial park on The Peterboro Project, a large Free-mo compliant exhibition layout that I built with Pierre Oliver.

Smithville taught me many lessons about layout design. Most importantly, it taught me that it’s easy to draw extra track, one more structure, or another interesting feature – but a lot harder to build them. It also gave me an appreciation of how a layout is a sum of all of these various parts, and that if I was going to invest the time to build each to the best of my ability, I’d better limit the number of “parts” I had to build.

I also learned that anything worth researching properly is also worth sharing properly. Smithville became the subject of the first ever clinic I presented at a convention – if I recall, it was the 2003 NMRA National in Toronto – and the focus of a two-part feature that appeared in the June and July 2005 issues of Railroad Model Craftsman magazine.